As I have written elsewhere, there is a musicological riddle that is often used to cut through the ethnographic complexities of cultural identity in contemporary Mauritania. To the complicated question of how to define a Moor (beydane) the simplest answer is ‘everyone who identifies with the music of Sidaty ould Abba’. Outside of Mauritania, his name only appears in articles about his famous daughter Dimi. In Mauritania, he is still considered the greatest beydane male vocalist of the twentieth century.

When I lived in Nouakchott, Sidaty had already retired from performing, accepting only exceptional invitations for national events or rare television appearances. The more I learned about Mauritanian music the more I kept hearing his name. I still remember the first time I heard one of his 1960s recordings. In the course of an evening drinking tea, one of Sidaty’s nephews offered to introduce me to him. On May 23, 2003, Sidaty ould Jeich ould Abba took me to meet his uncle Sidaty ould Abba. We were welcomed to the house by Sidaty’s son Ahmed. And for the next few hours Sidaty outlined his life in music and tested my knowledge of Mauritanian music, while his twelve-year-old daughter, Gharmi, made us tea.

When I lived in Nouakchott, Sidaty had already retired from performing, accepting only exceptional invitations for national events or rare television appearances. The more I learned about Mauritanian music the more I kept hearing his name. I still remember the first time I heard one of his 1960s recordings. In the course of an evening drinking tea, one of Sidaty’s nephews offered to introduce me to him. On May 23, 2003, Sidaty ould Jeich ould Abba took me to meet his uncle Sidaty ould Abba. We were welcomed to the house by Sidaty’s son Ahmed. And for the next few hours Sidaty outlined his life in music and tested my knowledge of Mauritanian music, while his twelve-year-old daughter, Gharmi, made us tea.

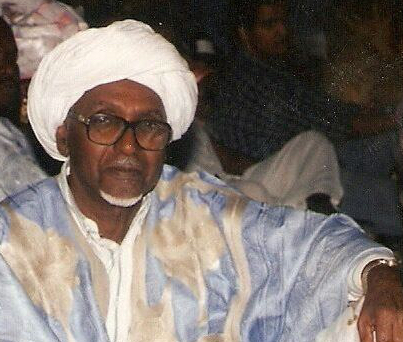

Photo by Michel Guignard

Sidaty ould Abba was born to Elva ould Abba and Gharmi mint Zemal in 1924, in a nomadic encampment near the town of Rachid, in the Taganit province. Sidaty was born into one of the Sahara’s great griot dynasties, he is the inheritor of the poetic and musical tradition of Seddoum ould Ndjartou. Both of his parents were talented musicians, with close ties to the Kunta tribe—one of the Sahel’s great tribes stretching from Mauritania to Mali. Elva taught Sidaty the basics of the tidinitt, drawing charcoal frets onto the neck of Sidaty’s lute to help him position his fingers. Sidaty learned the five modes, in all three of the tunings (the jamba el beyda, jamba el kahla, and the jamba el gnaydiya), that make up the traditional tidinitt repertoire. More than his instrumental skills, however, it was Sidaty’s voice that brought him glory. His mother Gharmi was a powerful singer whose style had a deep impact on him. Sidaty told me, however, that his mother ‘didn’t teach me to sing. No one can teach you to sing. You have to wait until the music enters your heart and you have to find your own voice.’

Sidaty spent his formative years performing for small gatherings under the Khaima kabira (big tents) of the Taganit’s noble families. He was one of the few singers whose voice was powerful enough to rise above the din of a wedding crowd. In 1958, Sidaty’s reputation caught up with him, when the Commandant de Cercle (Chimier?), the senior most French colonial official in the region, summoned him for a recording session in Tijikja, the capital of the Taganit region. This session was organized by a team from the French colonial radio station that broadcast to Mauritania from St. Louis, Senegal (the administrative capital of Mauritania until 1959).

A year later Sidaty was summoned once again by the Commandant de Cercle, this time they wanted Sidaty to fly to the radio station in St. Louis. Sidaty refused, he didn’t want to make any more recordings. His brother in law, Nagi ould elMoustaph who was an interpreter in the colonial administration, was sent to convince him. Sidaty soon buckled under the pressure and made the trip, flying from Tijikja to Nouakchott, and from Nouakchott on to St. Louis. It was during this trip that Sidaty was asked to record the national anthem. [Sidaty is known in Mauritania as the composer of Mauritania’s first national anthem. The melody was, in fact, composed by the French ethnomusicologist and composer Tolia Nikiprowetzky: he worked for many years for the Société de Radio-diffusion de la France d’Outre Mer; he also wrote one of the first pamphlets on Mauritanian music. Sidaty composed lyrics for the melody and arranged the composition for tidinitt.]

A year later Sidaty was summoned once again by the Commandant de Cercle, this time they wanted Sidaty to fly to the radio station in St. Louis. Sidaty refused, he didn’t want to make any more recordings. His brother in law, Nagi ould elMoustaph who was an interpreter in the colonial administration, was sent to convince him. Sidaty soon buckled under the pressure and made the trip, flying from Tijikja to Nouakchott, and from Nouakchott on to St. Louis. It was during this trip that Sidaty was asked to record the national anthem. [Sidaty is known in Mauritania as the composer of Mauritania’s first national anthem. The melody was, in fact, composed by the French ethnomusicologist and composer Tolia Nikiprowetzky: he worked for many years for the Société de Radio-diffusion de la France d’Outre Mer; he also wrote one of the first pamphlets on Mauritanian music. Sidaty composed lyrics for the melody and arranged the composition for tidinitt.]

Commercial photo for Boussiphone singles, Casablanca, 1967

This was the beginning of a mutually beneficial relationship: Sidaty’s voice gave Mauritanians a reason to listen to the nascent national radio and radio made Sidaty a legend. In June 1959, Mauritania’s national radio moved from St. Louis, Senegal, to Nouakchott. And once a year, throughout the 1960s, Sidaty travelled to the Mauritanian capital to record for the national radio. In 1964, the scholar H.T. Norris wrote, ‘In bygone days it was the skilled musician who praised warrior and reviled his foes. The griots, both men and women, now sing their airs with lute and harp into a microphone, and the master musician Sīdătī uld Abba, the improviser of the national anthem, has his fans in the remotest Saharan tent and palm-branch hut.’

As his reputation grew, Sidaty was invited to perform abroad. In 1962, he participated in a festival in France that featured artists from 65 countries. Sidaty was given the second prize, with the first going to a Spanish singer. Forty years later, he was still incredulous. He told me, ‘I asked the jury to start again, I couldn’t believe it, no one had a better voice than mine’. It was during this trip that a group of Mauritanian students gave Sidaty a steel string guitar. He brought the instrument back to Mauritania and was the first to adapt it to the Mauritanian modal system; his brother Cheikh was the first to record with the guitar. In 1969, Sidaty was part of the Mauritanian delegation that participated in the Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers, Algeria. Over the course of his career Sidaty also travelled to Senegal, Syria, and Saudi Arabia.

In 1967, Sidaty and his wife Mounina mint Eide travelled to Casablanca, Morocco, where they were invited by Mohammed Boussif to make a series of recordings for his Boussiphone label. Sidaty and Mounina spent several weeks in an apartment in the Boussif home and recorded enough material for Boussiphone to release eleven 45rpm singles. [Boussiphone also made a test pressing of a 33 rpm LP. I don’t know if the LP was released.] These were the only commercial recordings Sidaty made; they account for half of the commercial recordings of Mauritanian music released in the 1960s.

In the early 1970s, Mauritania suffered a series of extreme droughts. The annual rainfall in Tijikja fell from a historical average of 142mm per year to 58.8mm in 1971, 66.5mm in 1972, and 70.9 in 1973. These three years of drought accelerated the greatest sociological shift in the history of the Western Sahara, bringing an end to the nomadic lifestyle that had sustained itself for generations. The oases and ergs of Mauritania’s interior emptied as hundreds of thousands of Mauritanians moved to urban centres. Nouakchott was the fastest growing city in the country, with its’ 1965 population of 5,000 mushrooming to 134,000 in 1977 (435% growth). This dramatic population movement had an impact on griots; their patrons were moving to the city. Sidaty made the move in 1972, settling his family in the Medina Abattoir neighbourhood, (still known to many long-time residents of the city as Medina Sidaty).

Sidaty married Mounina mint Eida, a gifted singer from the Taganit’s other great musical family, in the early 1950s. They had three children, Seddoum born in 1955, Dimi born in 1958, and Ahmed born in 1959. Although all three of their children were gifted musicians, their daughter Dimi became Mauritania’s most famous and loved artist. Dimi’s voice was known to all Mauritanians, regardless of ethnic group, tribe, or region, and Dimi was the first Mauritanian artist to perform throughout the world, from North Africa to Asia, throughout Europe and the Americas. Sidaty and Mounina’s sons both did advanced degrees in France, Seddoum studied law and Ahmed economics. After completing their studies, both brothers laid down their guitars and pursued non-musical careers. In the early 1990s, Sidaty remarried. Sidaty and Zeinabou mint Mohamed Sidi also had three children, Garmi (born in 1991), Moulla, and Elva. Like her older sister before her, Gharmi was a child star, appearing on national television before her tenth birthday. And like Dimi before her, she has become the biggest star in Mauritania.

Within a few years, Sidaty’s home became a meeting place for music lovers. His daughter Dimi and his wife’s nephews Seddoum and Khalife ould Eide spent many evenings, in the mid-1970s, honing their skills and entertaining poets in Sidaty’s salon. Sidaty continued to record for the national radio throughout the 1970s, making his final recording in 1980, twenty years after independence. In recognition of his contributions, Sidaty received a lifetime stipend from Radio Mauritania. When Mauritania launched a national television station in 1984, Sidaty and his family recorded one of its’ first musical programs.

Sidaty ould Abba, Mauritanian television 1980s

Here is the entire performance featuring Dimi in her late 20s and her brother Ahmed ould Abba on guitar

As Sidaty adjusted to life in the capital city he realized that artists would need to sustain a wider network of patrons to support themselves. In particular, he understood that the state could be a source of patronage: the ministry of culture decided which artists were selected to represent Mauritania at international festivals, providing the only opportunities for international visibility (the Mauritanian diaspora wasn’t large enough yet to support visiting artists, that would come in the 1990s). Sidaty was convinced that for artists to equitably benefit from these opportunities, they needed to organize themselves. If not, all official invitations and government sponsorship would reflect the tribal affiliations of government officials, with ministers of culture only supporting ‘their artists’, those who had traditional patron-client relationships with the minister’s tribe. In 1969, in 1982, and again in 2002, Sidaty tried to organize Mauritania’s musicians into a federation or union. The first time at the urging of President Moctar ould Daddah and the subsequent times on his own initiative. When we spoke in 2003, Sidaty was discouraged; artists continued to put the ties of family and tribe ahead of corporate solidarity among musicians.

Sidaty ould Abba and his daughter Gharmi mint Abba

Starting in the mid-1990s, Sidaty limited his performances to special events; national ceremonies, important invitations, and occasional television appearances. He maintained his ties with his network of friends and patrons from the Taganit and spent time with his family, nurturing the talent of his youngest daughter Gharmi mint Abba. One of his final television appearances is one of my favourites, Sidaty shares his repertoire of tidinitt shwehr (melodies) and supports Gharmi.

Sidaty and Gharmi on Mauritanian television

Sidaty ould Abba passed away in Nouakchott on Thursday, September 26, 2019. He was 95 years old. He had been in poor health for several years, reportedly suffering from Alzheimer’s. Sidaty ould Abba’s musical legacy is carried forward by his daughter Gharmi, the greatest voice of her generation, as was her older sister Dimi’s before her, and their father before them.

This first recording is a cassette dub of two of Sidaty’s early 1960 Radio Mauritania recordings. My cassette is several generations removed from the master source. Clean copies of Sidaty’s earliest Radio Mauritania recordings are exceedingly difficult to find, including in the Radio Mauritania archives. I have been able to clean up some of the tape hiss but this remains a noisy recording. The first selection on Side A of this cassette is the best example of Sidaty’s extraordinary vocal abilities that I have yet heard. Listen to his vocal improvisation at the 2:30 mark. I have been listening to this for twenty years and it stills give me chills. This is intense and dramatic music. Sidaty’s tidinitt provides a frenetic ostinato and he sings with determination and passion.

Download Sidaty ould Abba - Radio Mauritanie 196? (320)

This second cassette was most likely recorded in the 1980s or 1990s. It features Sidaty accompanying himself on the acoustic steel string guitar. His voice has lost some of its high register and explosiveness, but it remains one of the most expressive and moving voices in Mauritanian music.

Download Sidaty ould Abba - Steel String (Wav)

Download Sidaty ould Abba - Steel String (320)

This second cassette was most likely recorded in the 1980s or 1990s. It features Sidaty accompanying himself on the acoustic steel string guitar. His voice has lost some of its high register and explosiveness, but it remains one of the most expressive and moving voices in Mauritanian music.

Download Sidaty ould Abba - Steel String (Wav)

Thank you to Sidaty ould Jeich for making the effort so many years ago and to Bamba ould Talebna for his insights and corrections. This piece is largely based on the conversation I had with Sidaty ould Abba in May of 2003. The picture of Sidaty in Casablanca was taken from a post by Fred Kramer of the Radio Martiko label.

Enjoy!

Thank you for the great music and tribute to a passed on legend. On this channel some of Sidaty and Mounnina's Boussiphone 45 singles can be found:

ReplyDeletehttps://www.youtube.com/user/fredulaah/videos

Think you Matthew

ReplyDelete